”

Prized at the Berlin Film Festival, this work belongs to the families and its mysteries. In particular, the director’s family and her grandmother Beatriz, who got married at 21 with the navy officer Henrique. With her husband away at sea, Beatriz raised their six children. And among them, Jacinto, the filmmaker’s father. To be a mother, to imagine, to live without freedom, everything is a creative and emotional metamorphosis in Vasconcelos’ first feature.

—

With a poignant first work, Catarina Vasconcelos brings us a portrait of a family, her own, narrated by its inhabitants and reinvented by her. Through letters, pictures, flowers, curtains, statuettes, puzzles and boats, a perfect universe is built, with life and death, but above all with the heart. And Catarina’s heart is resistant and strong, she is sweet and full of character, she has ambition and ingenuity. It allows each constructed frame (the film progresses through narrative sequences) to have its independence and be constructed through the character of each persona. A performative game with this playful characteristic, which is appeasement after play. The intelligence shown when the director hides behind the mirrors in the forest or when she climbs the mountains, pushing adversity to the limit when she tries to raise a tree, are ways of affirming an authorial and personal cinema made in the name of an enchantment and on the basis of oral tradition. Fly, Catarina, fly, because still live in your thoughts “all the exceptional things that build the universe of those who do not fear gravity”. (Miguel Valverde)

“

Cláudia Ribeiro spent seven months – since the time of plantation till the crops – capturing the work in the fields of the sisters Ana e Glória, in Passinhos de Cima, between the rivers Douro and Tâmega. It is an isolated place, where the baker, the fish seller, the grocer and their sons visit once a week. This a film on a way of life, the subsistence agriculture, but also about the humour and the ironies of representation and hospitality.

—

Claudia Ribeiro prints an everyday gaze at the tough agricultural work of Ana Rocha and Maria Rocha. The two sisters live in a village of 30 inhabitants in Passinhos de Cima, between the rivers Tâmega and Douro where they work from dawn to dusk, either in the rain or in the sun. Entre Leiras contemplates the relationship between them and the elements, but also among themselves, the synchronous work of the dibbles and rakes as well as picturesque conversations about country life. From the corn drying to the grape harvest, from the visits of friends and family to picnics in the shade, we follow the look of a camera that interacts with the two women and matures the relationship between characters and director. A circular sensation grows from two simple but tough lives, that follow the seasons as a vital substance to their existence. (Inês Lima Torres)

Sometimes neighbors play tricks and surprise us. Cesina Bermudes, a reformed obstetrics doctor, once knocked at Mire’s door offering help. The director thanked and, with her memory and creativity, returned the gentile gesture.

—

In an act of honest generosity, a 80 year old woman offers furniture to a younger neighbor that lived on Santos Dumont Avenue. In one morning, possibly spring, reading a newspaper clipping about a woman doctor that lived in the same avenue, that generous woman finally got a name: Cesina Bermudes. Doctor, obstetrician, researcher and feminist, “Painless Labor” is a portrait of someone that briefly passed through our lives but left a legacy that we try to unwrap. (Rui Mendes)

In 2013, Soares won a prize at Indielisboa in the section Brand New with the short animation film Outro Homem Qualquer. Now he returns to give image and sound to a precise moment of suspension: a sad man in his room facing a moment of indecision.

—

Still and alone, one man, another man, in a bed, at the window, let themselves be trapped in the air of things and in the body. Flies and flowers, keys, an atmosphere in motion in a space that breathes, quiet and broken, and sees the size of the gesture. The suspension is in line… Outside, the city repeats gestures, speeds up the mechanics; fall, leave, get up… isolate things, open your eyes, calibrate time. A film that knows how to wait. (Carlota Gonçalves)

Adapting a novel by the Portuguese writer Mário de Carvalho, Júlio Alves (Sacavém, IndieLisboa 2019) gives a bittersweet comedy about conjugal relationships, separations and communication. Arnaldo (Miguel Nunes) and Bárbara (Ana Moreira) want to end their relationship. We don’t know the reason, but we know they share the “paternity” of a turtle. Who will stay with the turtle? Where would it want to go? In this push-play game, the animal goes its way.

—

On the verge of rupture, doubt always arises. Júlio Alves’ first feature film is an adaptation of a work by Mário de Carvalho, an author that Alves has revisited in some of his short films. Now the universe is that of human relationships; – in this case, a couple is separating and goes through the always painful process of knowing who gets what, what belongs to who, who leaves and who stays, who is ready to compromise. Things are apparently not so bad, but who gets the turtle? The structure of the film is very well defined with an elegant composition of plans (Alves knows very well how to film closed spaces, specifically houses), the actors (the duo Ana Moreira / Pedro Lacerda) are very well directed always on the verge of suffering/apathy, and the montage has a correct rhythm that allows us to have the right information at every moment. And from there, just look in the mirror, because Júlio Alves hits us right in the eye. (Miguel Valverde)

In a laboratory, male mosquitoes are modified in order to transmit a lethal gene to the females. A man, a woman and a woman transgender live in a polyamorous relationship. Against the epidemic of the reactionary, the autonomy of intimacy and reproduction.

—

In times of epidemics that spread through mosquitoes, laboratories are genetically modifying these insects to contain their spread. In the background there are reports of cities occupied by military personnel who, in a display of strength, declare war on the enemy. Meanwhile, love persists and reproduces itself in logics that seem to contradict the binary thinking applied to nature. In a scenario of quasi-science fiction, we cross an unreal universe where music works together with the characters in the construction of the drama. (Margarida Moz)

After the première of Onde o Verão Vai: episódios da juventude (Berlin Film Festival, 2018) David Pinheiro Vicente continues with his sensorial cinema, of touch and gaze. Produced by Gabriel Abrantes, this is the Easter of growing up, desire and the flesh.

—

Diogo lives among angelic children and failed gown ups. Desire makes him grow up, despite all the childhood delights that still sing him lullabies. David (Pinheiro Vicente) also films between delicacy and dirt, i.e., between haunting sensations and the smell of blood. Then, everything gets stirred, elliptically and metaphorically, in a web tangled with fragments of what may be dreams, memories or visions (like the web of sexual innuendos connecting all the adult characters). At the center of the film a tension between death and guilt (which end up complementing each other in ritualistic sacrifice). (Ricardo Vieira Lisboa)

Seven years after Até Ver a Luz, Basil da Cunha returns to Reboleira to tell this story of returns, endings, a portrait of a youth and a social space. Spira, 18 years old, is back after years in a juvenile detention centre. Friends are still there, so are parties and schemes to make a living. Bulldozers tear down houses in the neighbourhood, Iara in the meantime became a woman, and drug trafficking is both a dream and a nightmare.

—

When Spira returns to Reboleira, eight years after his detention, he stands in what remains of the neighborhood he left. But he is not sure what is left of who he was eight years ago in that same place. It is in this duality that he will permanently test others and will be put to the test, especially by Kikas and his self-proclaimed authority as the leader of obscure businesses and supreme defender of the neighborhood and the people. If the city – and the country – already treat Spira as a stranger, where will he find an echo of belonging? The answer is perhaps in all the moments he dedicates to show his interest in Iara. A narrative that lives on the performance of non-professional actors, who add volume to the elegy that Basil da Cunha wishes to make in a space and time that are (not so) slowly disappearing from the urban map. An impure fiction that forces us to think about the reality of the non-places that populate cities, victims of policies that make their poetry ill and cast them in this dark never-ending night. (Mafalda Melo)

In Serra do Açor, Rafael Toral’s family works on the land. In particular, a task of renovation, after a devastating fire. Regada is an experience of immersion in the elements, everything lived through the senses, in a sonorous and visual landscape.

—

Water, fire, earth, air, green, brown, slug, dog, night, light. Francisco Janes’ work, marked by North American experimental cinema (he studied at CalArts), evokes the here and now of Peter Hutton’s landscape, the daily pictorialism of Nathaniel Dorsky and Paul Clipson’s natural symphonies. The result is an ode to the textures of nature (and digital medium), in a friendly confrontation with the abstractions of purely cinematic gaze. “Regada” crystallizes Janes’ intermediate path in the lyricism of labor and in the elements’ hypnotic becoming. (Ricardo Vieira Lisboa)

Rita Macedo (Implausible Things; This Particular Nowhere – IndieLisboa 2014 and 2015) lived in the nineties in Macau with her family. With a reflexive look, the filmmaker unites her memory and History. Both moments of the same finitude and transformation.

—

It could be said that Rita Macedo’s new film collides with her previous work. In fact, the confessional voice over and the use of images from home films belong to an essayistic intimacy that was unprecedented in her films. Nevertheless, her view remains intact: the fusion of ideas in the cosmic continuity of a discourse that is both purely factual (scientific even) and purely subjective (and memorialist). Where the ontology of thought was once questioned, now is the issue of writing history (and stories) that she examines. (Ricardo Vieira Lisboa)

Inspired by the diaristic cinema of Jonas Mekas, Malafaya organises the videos he’s been shooting for the past year and half of his life. A visual poem between the nostalgia of beauty and the hunt for images, between boredom and dancing.

—

Paulo Malafaya made this film in the school context of his course at Soares dos Reis Art School in Porto, opening a portal to a curious question: what will the director do next, since at such a young age he already manouvres the experimental, essayistic and diaristic language? Influenced by Jonas Mekas and Lukas Moodysson, this is a 17-minute flight that recounts one year and a half, using a hand-held camera and a montage that question and observe, that reposition concepts and offer the vision of a personal solar system. (Mafalda Melo)

)

The painter Ana Marchand always felt a bit dislocated in her family. The love of art and travel, where did she get those from? As a young woman she saw a travel book written by her uncle Maurizio Piscicelli and finally understood. Catarina Mourão (Pelas Sombras, A Toca do Lobo, O Mar Enrola na Areia) follows Ana’s familiar and spiritual journey. Who was Maurizio? Who is Ana? The face of one, the face of the other. Reincarnation are the several lives we live.

—

When she was a little girl, Ana saw a book written by her uncle Maurizio in the living room bookshelf. It was a book that narrated his trip to Congo, with photographs that made people dream. Afterwards, she lost track of the book and of the mysterious presence of that relative with whom she would discover to have a lot in common. Already a grownup, Ana will look for traces of Maurizio’s life, as someone searching for a piece of himself. Mourão will accompany this journey with her cinema, itself also an art of the voyage, many times physical ones, and others interior and emotional ones, triggered by photographs and pieces of memorabilia. Ana e Maurizio is a delicate circuit of gazes, a journey through palimpsest and the superposition between times, generations and images. Catarina observes Ana that, in turn, tries to look at what her uncle saw in his trip to Benares, India. Everything changes and nothing changes, we feel the wind of Rossellini’s cinema, but also the crossover of other Catarina’s journeys (Pelas Sombras; A Toca do Lobo). (Carlos Natálio)

Um dia João, jovem adolescente, decide não regressar a casa. Porque lá moram uma mãe infeliz e um pai ausente. Com Carlotto Cotta. Produzido por Luís Galvão Telles e Justin Amorim.

—

Crescer não é fácil, é um verdadeiro, (de verdade), grande cliché, ao qual não escapa o ‘moço’ desta história. Descobrir as actividades extra amorosas da progenitora, deixa-o num território de emoções confusas. Resta assimilar o jogo que está lá fora, a cumplicidade com os amigos, a bicicleta, um mergulho nas águas, um café nocturno; eis a fuga de um rapaz que está pronto a crescer. Um quadro narrativo delicado e sensível que segue o moço, observa-o, acompanha-o, e não o perderá de vista. (Carlota Gonçalves)

Paulo works in a bar and when his shift is over he wonders through the Lisbon night. Between a romantic and desolate tone, Flávio Gonçalves films in the poetry of the night. A poetry made of encounters, ferocious lights and bodies that love and fear.

—

Flávio Gonçalves’ beautiful and inspired return to behind the camera is made in the night-time continuity and in the (mis)match of male bodies. Paulo sends home his last customer at the bar and goes meet the boy of the intense gaze. The seeking carries on and the nocturnal lights of Lisbon do not let him down. Is this the time that love, pleasure and peacefulness finally align? A short film in multiple rounds, with a winning result. (Ana David)

A girl buys a tomato plant. She puts it in a vase too big for its size. The tomato plant gets depressed. It only gives one little tomato. But still it is time to say goodbye. Goodbye little tomato, see you sometime.

—

The simple life of a tomato tree that has finally fulfilled its mission. From all the attention it was given, a tomato was born – a single fruit. All the energy was consumed in the gestation of that life and it was time to harvest it, putting an end to a hope of abundance. (Margarida Moz)

A large group of people gather around a table for a meal. It is not clear whether they are family or friends. Food is served under a

noisy, atmosphere. Throughout the meal we discovered the various figures of the group, listened to their conversations and we can guess the connections between them. Toasts are made and congratulations are sung. At some point there are already those who sleep, who read, who date. The environment is increasingly fragmented. In the end there is only dirty dishes and silence.

—

Being at the table is a necessity for many. But describing a lifetime through a table is far more complicated. Fazenda, best known for his work in illustration, shows that it is possible to do it vigorously. Without dialogues and with a minimal chromatic quality, the film bets on Philippe Lenzini’s sound design, creating atmospheres to pay attention to the multiple stories brought about by the animation of Fazenda and that accumulate around this “Table”. (Miguel Valverde)

Ana Maria Gomes returns to Bustarenga, a village in the interior of Portugal, and starts to hear the usual “mantra”: “already with that age and still single and no kids?” A film about the social pressures and the places of a still dominant masculinity.

—

Ana lives in Paris but every summer she goes to a small village called Bustarenga in the interior of Portugal. She is 36 years old and single. What follows is a reflection on finding love through the lens and precepts of women in the village. Ana, wearing a yellow dress in the middle of the green landscape of this mountainous village, searches for prince charming. (Rui Mendes)

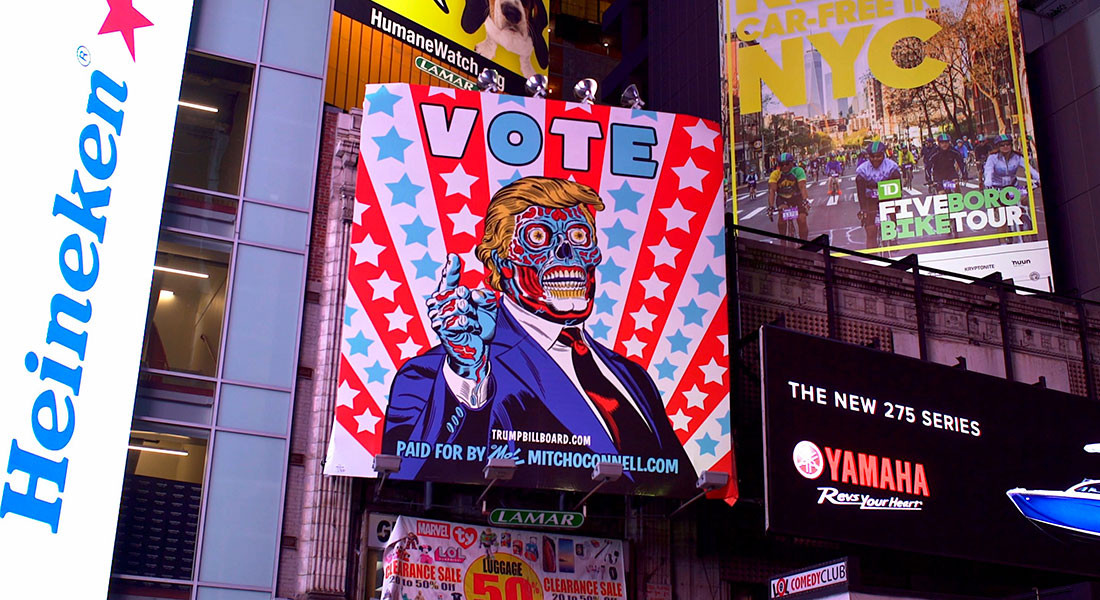

New York, 2020. A city caught in between the prophecies of John Carpenter (They Live; Escape from New York) and Trump’s supposed redemptive power. Skyscrapers point to the sky, but, at the same time, cage up like border walls.

—

And on his third short Francisco Valente exchanges Lisbon for New York, fiction for documentary, love for… No, one doesn’t exchange love for anything. But setting it aside for a while now, Valente winks at John Carpenter’s They Live, and with renewed robustness and a rigorous gaze films the city that never sleeps taken by a virus. Or is it two? When the night falls Moon River comforts us. A promise lingers in the air that everything will be all right, somewhere in the future. Skyscrapers will be there to witness to it. (Ana David)